By NollywoodTimes.com Chief Critic – December 7, 2025

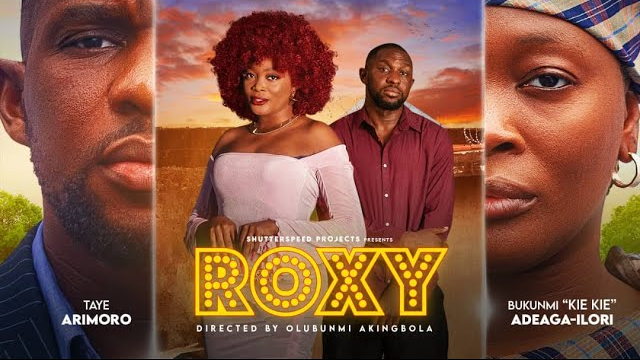

The latest socio-political drama out of Nigeria is not an easy watch, but ROXY forces Nollywood—and the world—to confront the harsh realities of survival, trauma, and the complex path to grace – Directed by Olubunmi Akingbola.

Picture this: A rain-soaked Lagos night, a streetwise hustler named Roxy kneels in her cramped room, whispering a raw prayer to the heavens – “Heavenly Lord, keep me from temptation, but if I no do this work, wetin I go chop?” In seconds, Biodun Stephen’s ROXY (2025) hooks you with that gritty authenticity only Nollywood does best. This 1:53:17 YouTube gem, dropped December 5 on BIODUNSTEPHEN TV, isn’t just another faith-romance flick – it’s a gut-punch exploration of compassion in Naija’s brutal survival game. Bukunmi Kiekie (Kie Kie) slays as Roxy, a woman torn between nightly “hookup work” and morning church anthems. Can one roadside rescue bankrupt her soul… or save it? Biodun Stephen delivers his 2025 redemption anthem – bold, heartfelt, and unapologetically Pidgin-powered. If you love Roses & Ivy vibes with deeper stakes, this is your next binge. Let’s dive in – no major spoilers yet, but buckle up!

ROXY is a landmark piece of African cinema, not because it introduces a new theme, but because of its unapologetic commitment to the psychological complexity of its protagonist. Forget the predictable moralizing; this film demands empathy for a woman who is both a devoted worshipper and a hardened professional, making it essential viewing for anyone interested in the evolution of African storytelling.

1. The Impossible Dichotomy: Faith and the Grind

The film opens with a scene that immediately establishes Roxy’s impossible world: she is praying, kneeling on her floor, begging God for grace. But this is no standard plea. She explicitly names her job—the “hook up work”—as a necessary evil, asking God not to take her “chop” (her livelihood) from her. It is a stunning, inverted covenant. She knows what she does is wrong by biblical standards, but starvation is a more immediate threat than eternal damnation.

This contrast is hammered home by the performance of the lead actress (whose name we must celebrate, even if uncredited here), who delivers a haunting rendition of a gospel song in church, only to transition instantly to defending her life choices against a pious, but ultimately unhelpful, neighbor. When the Evangelist urges her to “leave the hook up work and face God squarely,” Roxy’s response is the film’s first powerful gut-punch, delivered entirely in authentic, fiery Pidgin English:

“Make I leave the hook up work… so as my mate they gather they chop three square meal, make I gather they chop one square poverty every day?”

This single line—contrasting three square meals with one square poverty—cuts through decades of simplistic cinematic morality. It reframes her work not as a moral failing, but as an economic transaction required for physical, immediate survival.

2. The Catalyst and the Critique of Compassion

The narrative engine roars to life with the accident. Roxy, in a frantic moment, hits a man on the street. This seemingly random act of fate is the classic narrative inciting incident, but ROXY quickly uses it to expose the cracks in societal compassion.

The Hospital’s Burden

At the hospital, the doctor and nurse, representing the flawed system, immediately transfer financial and social responsibility onto Roxy. She protests vehemently, arguing she is being penalised for acting responsibly. The confrontation over the initial N50,000 bill is excruciatingly real. Roxy is trapped: the system demands she pay or face legal repercussions, even though the act of charity (rushing the man to the hospital) is what put her there. It is a cynical, yet true, portrayal of a community that praises the idea of good deeds but refuses to share the practical cost.

The Evangelist’s Flawed Advice

Later, the Evangelist sees the ordeal as “God showing you a sign that you should stop the work.” Roxy’s reply is a masterful deconstruction of privileged spirituality: “God dey give me sign make I leave that work by adding more bill to the one wey dey before?” This is a crucial scene, as it differentiates between the Evangelist’s well-meaning, judgmental charity (which requires a pre-emptive change in lifestyle) and the unconditional, practical charity that Roxy, despite her resistance, ends up demonstrating.

3. Bunny: The Blank Slate for Unconditional Love

The amnesiac man, whom Roxy eventually names “Bunny” because of his gentle features, is the film’s most potent narrative device. He is literally a blank slate, removed from the history and societal baggage that would usually judge Roxy.

An Amnesiac Mirror

Because Bunny has no memory, he cannot categorize Roxy. He does not know she is a sex worker, a church singer, or a street survivor. He only sees the woman who fed him, washed his clothes, and gave him shelter. This is the first time in her adult life she is seen without the filter of her profession or her past. This unburdened perspective allows him to initiate her transformation, not by force, but by simple respect and curiosity.

A brilliant, understated scene occurs when Bunny offers Roxy the N5,000 the hospital returned to him—a meager sum, yet the entirety of his worldly possessions. Roxy initially dismisses it, used to high transactional payments, but the pure, non-sexual intention behind the money forces a pause. It is a small act of gratitude that breaks her hardened exterior more effectively than any moral sermon.

4. The Unburdening: When the Past Becomes Present

The core emotional climax is Bunny’s simple, devastating question: “What happened to you?”

The resulting confession is the film’s tour-de-force, delivered in a rush of broken Standard English and anguished Pidgin. Roxy reveals she is a refugee from Cameroon and tells a harrowing story of losing her mother, working for families, and being repeatedly raped from the age of 13 by men who employed her. The most painful line is her realization:

“Why come be say when I house inside family say the man educated… I see evil pass.”

She details how she reached a point where she decided to take back control: “If you must touch my body, you must pay the amount where I go give you.” Her profession is not a choice of leisure; it is a calculated mechanism of defense and financial sovereignty.

This scene, lasting several minutes, is cinema at its most demanding and rewarding. It validates Roxy’s struggle and completely earns the viewers’ emotional investment. Bunny’s response—a declaration of love and a promise to build a future, not dwelling on her past—feels like the true act of redemption the Evangelist couldn’t offer.

5. The Ultimatum and the Flawed Finish

As Bunny finds employment (moving from arranging crates to doing accounting for a man named Max) and his self-worth stabilizes, the conflict shifts from external poverty to internal commitment. He attempts to manage Roxy’s life, first by offering to buy out her night’s work (promising her her ₦40k/₦50k rate) and then, later, by presenting the ultimate choice.

The Fight for Control

When the call comes from the “very big client,” the subsequent argument is phenomenal. Bunny issues the ultimatum: leave, and their relationship is over. Roxy, however, refuses to trade one controller for another. She rejects the idea that a man—any man, even the one she loves—can “dictate” her life. Her final words before walking out are heartbreakingly true to her character: “No man feel control me… now Me they dictate my life and me go tell myself say I don’t tire. I never tire.” She chooses sovereignty over stability, independence over love, in a move that complicates her “redemption” but makes her character deeply human.

The Sequel Setup

The final minutes, introducing the wealthy man Max (Bunny’s boss) and his fiancée Lisa, feel jarringly out of place. The film, having spent over 100 minutes in the raw, low-income world of Roxy, suddenly pivots to an elite, high-society setting. This sudden shift, while clearly designed to set up a sequel by providing the key to Bunny’s identity (the man he hit may have been Max himself, or Lisa’s ex), detracts from the emotional resonance of Roxy’s final decision. It sacrifices thematic closure for plot mechanics.

Verdict: The Power of Pidgin and a Painful Truth: ROXY is a brutal, beautiful film that succeeds because of its uncompromising authenticity. The masterful direction ensures that the use of Nigerian Pidgin English is not just an accent, but a vital tool for expressing emotion, rage, and truth that Standard English could never convey. It is a film that makes you deeply uncomfortable, not because of its subject matter, but because of how clearly it indicts the systems—both religious and economic—that create and sustain Roxy’s world.This film is a triumph of character-driven storytelling over moralizing. You need to watch it.

The Rating:………………………. 4 / 5

Call to Watch: Are you ready to see a story where the hero is simultaneously a sinner and a saint? Search for “ROXY – Nigerian Movies 2025 Latest Full Movies” on YouTube (Channel: BIODUNSTEPHEN TV) and prepare for a film that will stay with you long after the final, ambiguous shot. Let us know your thoughts on Roxy’s final choice in the comments!

#NollywoodTimes

#ROXYNollywood

#BukunmiKiekieROXY

#Nollywood2025

Leave a Reply