The Gold Standard of Marital Decay: An Introduction

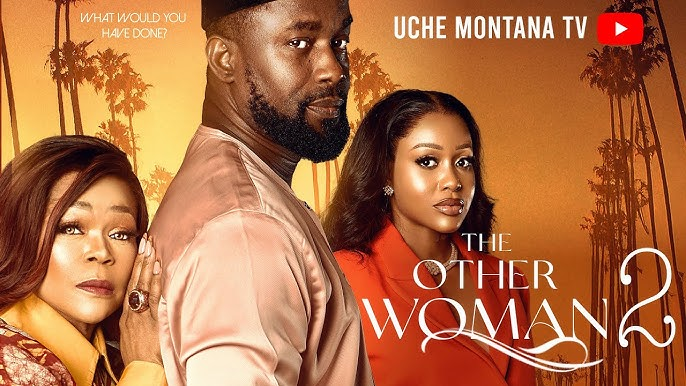

When a Nollywood movie title includes the word “infidelity,” the audience often braces for predictable melodrama, catfights, and moralistic sermonizing. But “The Other Woman 2,” starring a triumvirate of talent in Shaffy Bello, Uche Montana, and William Benson, is not that movie. It is, instead, a masterclass in controlled combustion—a slow, deliberate unravelling of a marriage so meticulously constructed that its collapse feels less like a tragedy and more like a necessary, cleansing apocalypse.

Clocking in at over 100 minutes, this film asks a difficult question: What happens when the biggest lie in a marriage isn’t the cheating, but the 25 years of silence that made it inevitable? This review dives deep into the film’s narrative sophistication, its stunning performances, and the sharp social commentary that elevates it beyond the genre and into the realm of essential African cinema. Get ready, because The Other Woman 2 is not just entertainment; it’s an indictment of high-society marital tradition.

I. Narrative and Thematic Depth: Beyond the Mistress Trope

The structural genius of The Other Woman 2 lies in its subversion of the central conflict. The film cleverly sets up the expectation of a venomous confrontation between Queen (Shaffy Bello), the wife, and Amanda (Uche Montana), the mistress. Yet, the true battle is internal and thematic. The narrative uses the infidelity of Frank (William Benson) not as the plot, but as the catalyst that forces both women to confront deeper, systemic issues in their lives.

The True Conflict: A Man’s Deception as a Shared Wound

The movie’s opening—Amanda at Queen’s dinner table, frantically silencing her constantly ringing phone (which, unbeknownst to Queen, is Frank)—establishes the unbearable tension built on deception. This scene masterfully communicates that Frank is not merely cheating; he is playing both sides, actively and selfishly controlling the reality of two intelligent women. The tension is almost unbearable, a silent, slow-burn introduction to a situation fueled by Frank’s calculated absence and Amanda’s crippling realization.

The narrative excels by making Amanda a victim of Frank’s lies just as much as Queen is a victim of his avoidance. This shared wound creates thematic complexity. The narrative asks whether a marriage built on “duty” and “avoidance of conflict,” as Frank confesses, is morally superior to a relationship built on a lie. By prioritizing the internal journey of both women, the script refuses to let the audience settle for the comfort of assigning simple villain and hero roles, demanding a more nuanced understanding of culpability.

Pacing and Structure: A Justified Runtime

At 1 hour and 40 minutes, the film is deliberately paced, but it never drags. The slow, almost theatrical staging of the early acts—Queen’s counseling sessions, Frank’s listless return, Amanda’s friend Nick’s “reality checks”—are necessary build-up. They allow the audience to absorb the suffocating wealth and emotional distance that define the Craig home.

The pacing is structured around three monumental confrontations (Amanda-Queen, Amanda-Frank, and Queen-Fesus), each acting as a sharp narrative jolt that justifies the extensive runtime. The momentum peaks with Amanda’s final, dignified exit from Frank’s life, followed by the sobering blow of Fesus’s truth, which recontextualizes Queen’s entire existence and validates the slow, meticulous build-up of the film’s emotional scaffolding.

II. Characterization and Performance: The Power of Three

The film’s success rests squarely on the shoulders of its principal actors, who navigate complex emotional territory with commendable restraint, transforming what could be stock characters into layered portraits of disillusionment.

Shaffy Bello as Queen: The Dignity of the Last Word

Shaffy Bello delivers a towering performance that is less about crying and more about the crushing weight of shattered pride. Her character arc is the film’s most compelling journey. We initially see Queen as the imperious society matriarch, perfectly coiffed and utterly controlling, living up to the description Frank later gives Amanda.

Bello beautifully navigates the shift from denial and aggressive vengeance (when she spontaneously fires her entire domestic staff) to the quiet, heartbreaking self-reflection triggered by Fesus. The transformation is entirely earned. It is not Frank’s apology that changes her, but the external, objective view of her life provided by Fesus and Amanda. Queen’s final decision to separate, not out of rage but out of a need for dignity and self-preservation, is the film’s decisive victory for the modern African woman.

Uche Montana as Amanda: The Moral Reckoning

Uche Montana as Amanda successfully avoids the caricature of the manipulative “home-wrecker.” She is portrayed as a genuine woman seeking love, whose betrayal is magnified by her forced complicity in Frank’s lies. The scene where she realizes she was with Frank on his 25th anniversary is a visceral moment of self-disgust.

Montana’s performance shines brightest in her final confrontation with Frank. Her lines—”This thing between us can never be called love. Love doesn’t start with lies”—are delivered not with melodrama, but with a firm, painful finality. Her final, quiet apology to Queen is a stunning moment of grace, solidifying her character’s moral recovery and driving home the film’s core message: she values dignity over desire, concluding that even a love as sweet as theirs “is never enough” when built on deceit.

William Benson as Frank: The Flawed Antagonist

Frank is deliberately written as an emotional vacuum, a man who is the center of the conflict but contributes nothing but avoidance. William Benson plays this role with a weary listlessness that speaks volumes. Frank is not a villain; he is a coward, using his wife’s perceived “controlling” nature as an excuse for his lack of courage to pursue happiness or, more accurately, simple peace.

His justification—that Amanda “made me feel like a man”—is the classic, tired trope of the male philanderer. The script, however, uses this trope to expose the system of male entitlement and the patriarchal expectation that a wife must tiptoe around her husband’s ego. Frank is the vehicle of pain, and Benson’s understated performance effectively conveys his utter inability to take responsibility for the decay of his own life.

III. Direction and Technical Execution: Staging the Emotional War

The film’s technical competence ensures the focus remains on the dramatic core, with the direction enhancing the emotional impact of the key scenes.

The Power of Confrontation

The staging of the confrontations is impeccable. The most emotionally charged scene is the Amanda-Queen confession. Shot in a public but quiet space, the camera holds close on both actresses as Queen’s initial denial gives way to disbelief and then volcanic bitterness. The dialogue, which rapidly shifts from apology to verbal warfare (“You have sown a seed, and you will harvest in your marriage one day!”), is sharp and devastating.

However, the most narratively impactful scene is the Queen-Fesus reality check. The director stages this exchange with immense respect, focusing on the unexpected gravitas of the staff member. This scene, where the truth of Queen’s managerial tyranny is laid bare by an objective observer, is a moment of pure genius, acting as the final, unvarnished piece of evidence Queen needs to dismantle her self-image.

Aesthetic and Production Value

The production value is visibly high, with opulent, spacious sets (the Craig residence) that serve a thematic purpose: this marriage is a gilded cage. The cinematography is clean and focused, using framing to emphasize distance and isolation. Frank is often shot alone, shrouded, or physically distant, emphasizing his emotional withdrawal. The recurring soundtrack, while leaning on the sentimental, underscores the melancholy of lost love and shattered promises, enhancing the overall drama without overwhelming it. The dialogue, particularly in the exchanges between the friends, is conversational and authentic, ensuring that the heavy themes land with realism.

IV. Cultural Context and Social Commentary: A Paradigm Shift

The Other Woman 2 is perhaps most successful in its biting social critique, challenging both the traditional Nollywood narrative and the realities of marriage in elite Nigerian society.

Subverting the Infidelity Trope

Unlike countless predecessors that portray the mistress as an inherently evil, destructive force and the wife as a saintly victim, this film positions both Queen and Amanda as casualties of Frank’s systemic dishonesty. The moral burden is rightly placed on the systemic lie that kept the marriage functioning—or rather, dysfunctional—for decades. This is a progressive step for Nollywood, suggesting that blame in a failed marriage is often multilateral, extending beyond the bedroom to the foundation of respect.

Fesus: The Voice from Below

The scene involving the butler, Fesus, is arguably the film’s most potent piece of social commentary. By making the hired help the reluctant bearer of the uncomfortable truth, the movie acknowledges that high-society dramas are often transparent to those serving them. Fesus’s revelation—that he watched the staff disrespect Frank because his authority was constantly undermined by Queen—is a profound moment of class-based critique. It forces Queen, and the audience, to acknowledge that privilege and control can be just as corrosive to a marriage as betrayal.

The Choice of Dignity: Modernity Wins

The film ultimately takes a modern stance. Queen, pressured by society to uphold the “25 years” of marriage, chooses individual dignity over societal duty. She does not take Frank back, even when he begs for forgiveness and promises change. Her decision to tell him, “No one makes a fool of Queen Oliday Craig. Not even you,” is a powerful rejection of the traditional narrative where the wife must sacrifice her self-respect for the illusion of a family unit. She chooses a clean break, reclaiming her power by allowing him the entitlements he sought, while keeping her own peace. The film’s message is clear: the foundation of a marriage is self-respect, not merely a promise made on a wedding day.

Verdict & Rating: A Triumphant Marriage Drama

The Other Woman 2 is a meticulously crafted, emotionally resonant film that dissects the anatomy of a failed marriage with maturity and sharp insight. Supported by phenomenal, career-defining performances from Shaffy Bello and Uche Montana, the movie uses the familiar terrain of infidelity to launch a powerful critique of control, ego, and the cost of maintaining a lie. It is a film that will generate difficult but necessary conversations.

A must-watch for its intelligent script, stunning lead performances, and courageous thematic choices.

Rating: ………… 4½ (4.5/5 Stars)

Call to Watch

Have you ever wondered what happens when the “other woman” and the wife finally talk? Do yourself a favor and stream The Other Woman 2 right now. Then, come back and tell us: Was Queen right to divorce Frank, even after 25 years? Let us know in the comments below!

#NollywoodTimes

#TheOtherWoman2

#NollywoodDrama

#DignityOverDuty

Leave a Reply